Was William Blake a Feminist?

“Lift up your skirt and speak!”:

Deconstruction of Patriarchy in William Blake’s “The Sick Rose”

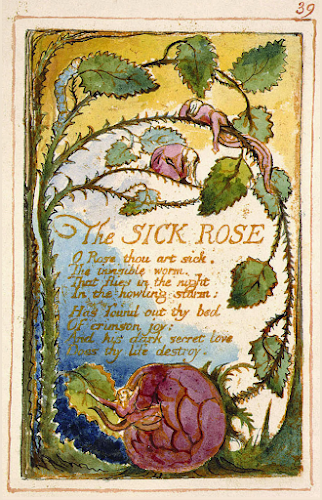

Figure 1: Vase holding two roses and scattered petals

“Her libido is cosmic, just as her unconscious is worldwide” (Cixous

889). Now that’s a quote worthy of being framed and hung in the living room! It

would go unnoticed in the children’s room, but on the other hand, the adults

would pay it too much attention. Even those who don’t understand the

implications of Helen Cixous’s outcry against masculine oppression would feel

the need to add their unnecessary input about someone else’s house décor.

Although, honestly speaking, no one would put up a quote about the libido whether

it be their own or someone else’s, simply because society has programmed individuals to censor thoughts which simply do not comply to patriarchal ideology, and expressing sexual desire is one of those thoughts. For instance, in

a patriarchal society, females can not express sexual desire because they are

to be void of sin and sexuality. Despite of masking the disillusionment of naivete and foolishness with purity, this child-like innocence is greatly challenged by

life’s experiences and indicates to a shift which accepts the cruel society and

learns to bend the rules to one’s pleasure. Built on the marriage of these

ideas, William Blake presents the “Songs of Innocence and Experience” which

explore the defiance of 18th-century

conventions. Despite being a legacy in modern popular culture, his attitude

towards gender is met with criticism as it fails to recognize the autonomy of

female experience. According to Mellor, Blake’s gender politics conform to

those of other Romantic poets, that is the “male imagination can productively

absorb the female body” (23). Although when deconstructed, this text’s

apparent anti-feminist bias collapses and subverts those prejudices through

language, establishing new readings of his work. In “The Sick Rose”, Blake’s

images of sexual difference affirm rather than undermine the passive side of

the male/female hierarchy. This essay will argue that the poem’s overt

ideological project - the condemnation of feminine sexual liberation, which is replaced

by the assertion of a traditional patriarchal role - is undermined by the text's own ambivalence towards the binary opposition on which that ideological project rests, conformity/nonconformity towards heteronormative traditions. This ambivalence finds

its most conflicted expression in the characterization of the ‘Rose’, the

embodiment of the poem’s covert fascination with the heterosexual narrative it condemns.

This deconstructive reading explores Blake’s poetry using criticisms such as

psychoanalysis, feminism and gender theory to debase the patriarchal tone of

the text and produce different interpretations representing his ideas of

society, man, and woman (Senaha 85).

In “The Sick

Rose”, the binary opposition structuring the text can be found through the

disagreement between Blake’s heterocentric attack on domineering female will and

the presentation of autoeroticism where the female rejects traditional

relationships between the sexes. The female’s refusal of traditional gender roles

which “cast men as rational, strong, […] and decisive; [and] cast women as

emotional (irrational), weak, nurturing and submissive” (Tyson 25) is the

consequence of repressing finding expression in perversity. In “The Sick Rose”,

the ominous rhythm of the short, two-beat lines contributes to the unflinching

poetic voice of dread. The poem consists of two four-line stanzas and starts

with the speaker's startling voice:

O Rose, thou art sick.

The invisible worm,

That flies in the night

In the howling storm:

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy:

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy. (39)

The first line of the poem

“O Rose, thou art sick” (1) uses “thou” (1) to address and personify the rose. The

red flower is an archetypal symbol for feminine love due to its recurrence

throughout the history of Western literature. Therefore, the rose can be viewed

as a heterosexual female as patriarchy is centered strongly on the belief of

compulsory heterosexuality. The watching of the female shows that she is

subject to the male gaze where the “man looks [and] the woman is looked at”

(Tyson 102). By reinforcing male control, the speaker’s view of women as merely

tokens or commodities in a male economy stresses the common act of direct physical

appropriation of females which is the reduction of women to the state of

material (Guillaumin 74). The first line is rich in patriarchal culture

as it encompasses the speaker’s contempt towards liberation of femininity and oppression

of the rose through what are supposed to be ‘rational’ and ‘strong’ actions.

Moving on, the “invisible worm” (2) is a phallic symbol which introduces a male

presence in text. The cylindrical shape of the parasite recognizes the

archetype of a snake which is an image of evil and corruption associated with

the reptile from the Bible. When combined, “the invisible worm” (2) is a

traditional symbol of male power which embodies destruction and masks its true

snake-like nature under the false pretense of the worm. When taken literally

line 3 and 4 do not present a cohesive argument so they must be studied according

to the rule of metaphorical coherence, so the metaphors behave consistently

with the context of the work (Tyson 232). The dark nature imagery alludes to

the male moving at night, trying to hide his actions by moving in haste as

indicated by the verb “flying” (3). The howling storm serves two purposes: to

foreshadow to the unfortunate events about to unfold and external natural

forces trying to prohibit the actions. Regardless, the man can ‘worm’ through

the night, governed by his id which is his “desire for power, for sex, for

amusement [...] -- without an eye to consequences” (Tyson 25). A sudden shift

from soft anticipation in the first stanza to harsh domination in the second

stanza occurs in the tone when the worm finds “thy bed” (5). The revelation of

the sacred place paints an image of the worm finding the flowerbed

simultaneously it alludes to the man finding the woman’s bed. Followed by “of

crimson joy” (6), the speaker helps to identify and unite the underlying

connotations of all lines above. Crimson is a symbol of blood which when used in

association with the female can symbolize ‘loss of virginity’ or the ‘reaching

of maturity’ through menstruation, both events cause the loss of a vital body

part, so crimson has a negative connotation. Considering the order of actions,

we can confirm the loss of purity which is further accentuated by forcing of

the male into the female’s sacred place, underlies a non-consensual sexual relationship.

Through the juxtaposition of the female’s unpleasant experience, “crimson” (6),

and male’s pleasant experience, “joy” (6), the speaker reveals that the

pleasure of the worm is dependent on hurting the rose. In addition, “and his

dark secret love” (7) uses dark imagery to hide the rape of the woman and shows

the male’s interpretation of love as something that can take advantage of the

female even if she suffers. The last line “does thy life destroy” (8) connotes

decadence and provokes the rose’s decay. Even though the rose physically

submits to patriarchy, she is still objectified by the same patriarchy. The

female is placed on a pedestal where she suffers physical punishment from the

community if she shows sign of being inadequate or unnatural (Tyson 90) as

shown by the sick condition which leads to the rape of the rose. All together,

the poem conveys the message of inborn inferiority of women which is referred

to as biological essentialism. Due to this inborn inferiority, the female does not

struggle against the abuse because she conforms to the heteronormative

patriarchal ideology where it is her job to serve the men. This concept is

reflected throughout the text as the speaker observes the scene

of non-consensual love-making and has no intentions of stopping the act from

unfolding.

Juxtaposed

against the oppression of women by patriarchal ideology is the presentation of

the denial of heterosexual actions which would serve as an enactment of

liberation. One of the most effective ways in which the text undermines the

patriarchal attitude is by using ambiguous diction and a harsh, sudden tone

towards the female. In the poem, the speaker, a witness of the woman's masturbation, keeps distance from the scene and describes it with surprise and

a warning. “The first line arises the question that if the heterosexual

interpretations are accurate, how can Blake blame the Rose, a rape victim, of

being "sick" (1), without accusing the worm of being a

"rapist" (Pagliaro 5) or the "traveller who moved 'silently and

invisibly' on the winds of seduction" (S. Gardner 110). The worm might be

called sick because its actions are unethical. The Rose cannot be a temptress

either, unless she is willing to seduce the traveler whose "dark secret

love, [she knows eventually] Does [her] life destroy (7-8)”” (Senaha 93). The poet

passionately proclaims his disapproval of her actions as he finds her nymphomaniac

habit that is sorely sickening her genitalia to be an illness. Theses actions

of self-pleasure interrupt the discourse of the archetypal image of the worm.

Indeed, it is the idea of a "worm" (2) as a sexually destructive

flesh, as well as the pronoun "his" which implies the worm is male,

but this assumption has led critics to interpret the whole poem in terms of

illicit sexual intercourse. Unsurprisingly critics have ignored the

implications of “invisible” (2) when it is key to the poem as if it was simply

not there. "Invisible" (2) means anything that is visible is not

apparent to the senses, so the invisible worm becomes a result of imagination; an

unconscious act of displacement to “represent a more threatening person, event or

object” (Tyson 18). So according to Jacques Lacan’s theory, the ‘worm’ is

not a literal worm nor an actual person but a metonymy for something which only

Blake and the woman can imaginatively see and describe.

The natural imagery of ‘flying in the night, in the howling storm’ pulls the

reader out of the action scene and thrusts us into the surroundings. “Howling

storm” (4) is used to describe the loud commotion of natural forces or

prolonged wailing outcry of human beings which are trying to prohibit the

female's act of sexual liberation but like the initial analysis, fail to do so

as the female’s bed is already “of crimson joy” (6) before it is found out.

Through the order of events, the speaker reveals that the rose is less

innocent, as she uses her worm-like finger to reach her climax before the

wailing of people reaches her, and thus “she enjoys the self-enjoyings of

self-denial, an enclosed shelter of self gratification (Senaha 88). Since

her habit is a "dark secret love" (7) of autoeroticism, the speaker,

who opposes this kind of narcissism, prophesies that her finger's obsessive secret

love will destroy her life, just as the pictures of the roses in the art-piece

are worm-eaten to death. An interesting artistic choice by Blake is the

exclusion of thorns in poem even though he illustrates them in his art. This

emphasis on the refusal of association with male imagery even when the female

succumbs to the need for pleasure stresses the collapse of the patriarchal

reading of the poem. For Blake, the censoring of the female body is important

as it allows him to demonstrates a woman's "secret love" (7) in a way

so he could survive and, as a result, defy the late eighteenth-century sexual

censorship, as Srigley mentions that "it was precisely such an

investigation into the taboos surrounding sex in his own age that Blake

undertook" (5). His antipathetic presentation of autoeroticism reflects

his strong belief in mutual love. His early idea of sex is known for its

liberalism, and because of this belief, the poet opposed autoeroticism. For

him, sex is a device to express his idea of free love, which should not be restricted

by any social obstacles such as marriage. Free love is his metaphoric

expression of spiritual freedom. Making love with another, therefore, becomes a

cooperative action of achieving the ideal freedom. In "The Clod & the

Pebble” (31) Blake says, "Love seeketh not itself to please […] but

for another gives its ease, and builds a Heaven in Hell's despair", which

is followed by "Love seeketh only self to please [..] joys in another's

loss of ease, and builds a Hell in Heaven's despite". This statement of

"the paradox of love, in its selfless innocence and selfish

experience" (Davis 55) reveals Blake's consistent belief in mutual love. He

emphasizes the unselfish giving of love, which is necessary to mutual love.

Therefore, Blake considers the sexual action more spiritual than physical. On

the other hand, he disapproved of self-pity or self-love. The latter merely

produces temporary physical pleasure and ends with nothing to cherish for the

future: autoeroticism connotes narcissism, selfishness, indifference to others,

and escape from reality. In "The Sick Rose", Blake presents all these

meanings in eight lines and accuses the woman of being self-enclosed, "0

Rose thou art sick” (1). As an artist, Blake hid his message in the picture of

roses and drew the woman's finger, a substitute for her imaginary man, as if it

had merely been a rose-eating insect. As a poet, he wrote so that people would

innocently appreciate the poem as a description of a naturalistic decay of the worm-eaten

roses, or, probably, as that of a barely tolerable sexual scene.

William Blake

is well known for toying with the definitions of what society should and

shouldn’t look like. By using his talent in the realm of writing and art, he

tries to uncover some of the wrongdoings in England during the 18th century.

“The Sick Rose” condemns the masculine control over women’s sexuality, and

instead paints a picture which allows the female to receive self-pleasure while

denying the heteronormative expectations placed on her. When read in the

context of a patriarchal speaker, the text equates femininity with submission,

encouraging women to tolerate abuse if they are ‘sick’, mentally or physically.

The desire for control over women is well served by patriarchal ideology as every

form of expression is to “accommodate art to patriarchal expectations or face

the consequences” (Tyson 90). In contrast, the second reading does not conform to the traditional gender roles of pleasing the male, instead

the presentation of autoeroticism serves to break free from patriarchal

expectations placed on females. This reading is more convincing because the

tone of the speaker aligns with Blake’s disapproval of selfish self- pleasure

and the illustration works to strengthen the act of feminine sexual liberation.

By showing how the literary work quietly collapses the binary opposition of the

obedience and resistance against heteronormative traditions, Blake calls for a

rational abandonment of a harmful tradition which works to exploit the female gender

and to detach oneself from ways of thinking which restrain our freedom of

expression. Clearly, there is an important connection between the theme

discussed in this paper and the real-life situations occurring all over the

world these days. Recently the MeToo movement, a movement against sexual

harassment and sexual assault, has caused an uproar in society while trying to

give a voice to the silenced. It has received a lot of backlash due to the

suspicion which lies in asking us to reassess our most personal experiences and

our most entrenched and comfortable assumptions. This movement has spread

rapidly through social media and exposes how common assault has become, just

because most people have turned a blind-eye to it, there are others who have

the strength to speak on the behalf of the silenced ones. Before the movement,

victims would sit still, like flowers in a garden unable to move or speak out,

while the offenders would move freely like parasitic worms looking for new

victims, but now, the victims are starting to gain more confidence in

themselves as the criminals are being held responsible for their unethical actions.

On the surface, it’s impossible to tell how many worms have chewed through rose

petals because they are almost always decorated with rips and tears, which

eventually lead to their death as if infected by the plague. This is simply

because we forget we have thorns, we’re all born with them, we just forget to

sharpen the blunt ones after the sharp attacks of society.

Works Cited

- Cixous, Hélène, et al. “The Laugh of the Medusa.” Signs, vol. 1, no. 4, 1976, pp. 875–893. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3173239.

- Anne K. Mellor’s Romanticism and Gender: Mellor, Anne K. Romanticism & Gender. Routledge, 2009.

- Senaha, Eijun. “Autoeroticism and Blake: O Rose Art Thou Sick!?” The Annual Reports on Cultural Science, vol. 46, no. 1, 30 Sept. 1997, pp. 85–109. Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers, hdl.handle.net/2115/33690

- Tyson, Lois. Critical Theory Today: a User-Friendly Guide. 2nd ed., Routledge, 2009.

- Blake, William. Songs of Innocence and of Experience. [A Facsimile of a Coloured and Gilded Copy of the First Edition.]. 1923. Print.

- Guillaumin, Colette. Racism, Sexism, Power and Ideology. Taylor and Francis, 2002.

- Pagliaro, Harold E. Selfhood and Redemption in Blake's Songs. Pennsylvania State Univ Pr, 1987.

- Gardner, Stanley. Infinity on the Anvil. Blackwell, 1954.

- Srigley, Michael. “The Sickness of Blake’s Rose.” An Illustrated Quarterly, vol. 26, no. 1, 1992, pp. 4–8., bq.blakearchive.org/26.1.srigley.

- Davis, Michael. William Blake. London: Paul Elek Ltd, 1977. deVries, Ad. Dictionary of Symbols and Imagery. London: NorthHolland Publishing Company, 1984.